A new study makes it possible to better understand how the pandemic virus causes depression, anxiety and loss of concentration known as “brain fog” in patients that develop long.In most individuals, the virus, SARS-COV-2, is successfully eliminated by the immune system, but some fight against prolonged complications, the cause of which is unknown.

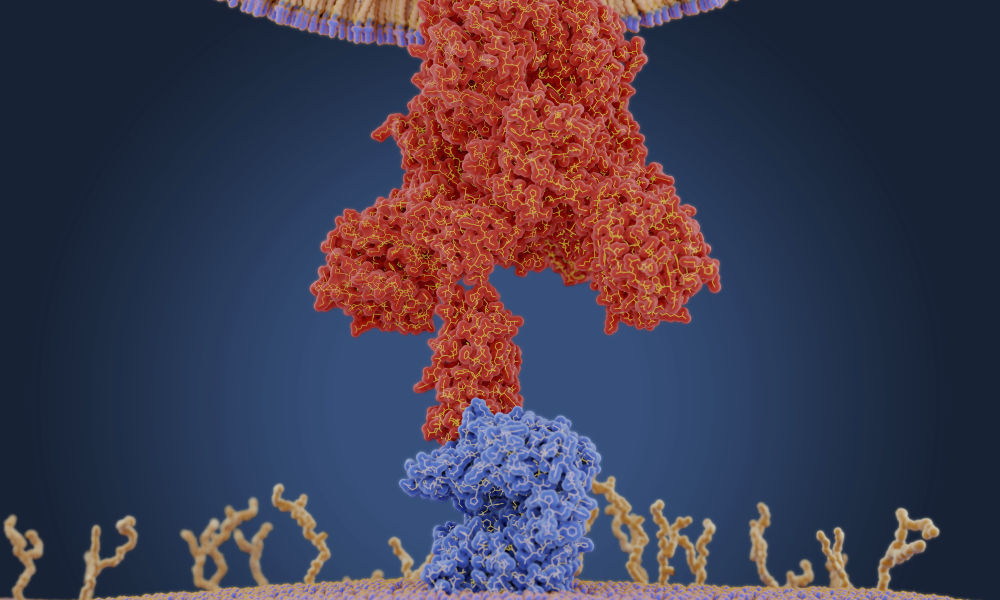

Directed by researchers from Nyu Grossman School of Medicine, the study, who examined hamsters and human tissue samples, revealed that, well after the end of initial viral infection, the deepest biological changes Produce in the olfactory system, composed of the nasal cavity, the specialized cells that line it and the region of the adjacent brain which receives an entry on odors, the olfactory bulb. While a recent study of the same laboratory showed how Sars-Cov-2 infection hinders smell by modifying the activity of certain olfactory proteins (receptors), the new study reveals how the immune reaction sustained in olfactory tissue Affects brain centers that govern emotion and cognition.

Published online on June 7 in Science Translational Medicine, the study is the first to show that the hamsters previously infected with the Sras-COV-2 develop a unique inflammatory response in the olfactory fabric, say the authors of the study. Unlike a large part of the COVVI-19 research published to date, this study has complicated the way in which the answer to the SARS-COV-2 in the Hamsters compared to the influenza A, the virus responsible for the pandemic of the ” Porcine influenza “in 2009. In particular, the study revealed that while the two viruses generated a similar answer in the lungs, only Sras-Cov-2 sparked a chronic immune response in the olfactory system which was still obvious a one month post-violence.

This chronic inflammatory state observed with the Sras-COV-2 corresponded to an immune cell disorder such as microglie and macrophages, which clean the debris left as a result of the dead and dying olfactory lining. They recycle this material but also trigger additional cytokine production, pro-inflammatory signaling proteins. This biology was also obvious in olfactory tissues drawn from autopsies in patients who had given themselves initial infections of COVID-19, but who died of other causes.Systemic effectsThe SAR-COV-2 virus and the flu naturally infects hamsters and humans-lasting around 7 to 10 days for the two hosts, according to the researchers. In this study, the authors examined genetic and tissue changes at 3, 14 and 31 days after infection to examine acute and persistent responses to these infections. Previous studies have shown that the golden hamster model is better copying the human biological response to sras-cov-2 than mice, for example, in which infections require that the virus or the mouse is modified for the infection to happen .

The research team found that the Sras-Cov-2, because of the oddity in the way the virus is copying, probably causes a stronger immune reaction than the same amount of influenza A, which can explain the scars Most important caused by SAR-COV-2 in the lungs and kidneys of hamsters 31 days after the initial infection. The results have also confirmed that the prolonged immune reactions observed in a long coconut occurs in the tissues where the Sars-Cov-2 virus is no longer present. One of the theories of the team is that the damage caused by the initial infection have left remains of dead cells and fragments of viral RNA, which cause prolonged inflammation. They also consider the possibility that significant damage to the lining of olfactory cells, responsible for the loss of odor observed with SRAS-COV-2, could give bacteria access to the cells to which they would not be exposed (for example, the Brain cells in the bulb), which would then trigger immune reactions.

Whatever the cause, the chronic immune response in the olfactory tissue of hamsters infected with SARS-COV-2 was accompanied by behavioral changes that study authors followed with established tests. For example, the SARS-COV-2 group’s hamsters were faster to stop trying to swim, a depression measure or to react to foreign objects (balls) in their cages, behavior linked to anxiety. Depression and anxiety are common attributes of the long cocovone, and these behavioral anomalies have proven to be correlated with unique changes to brain cell biology, according to researchers.

Beyond the brain, the authors examined the lungs a month after clearance of the virus and after each acute pulmonary infection. They found that following the SRAS-COV-2, the reconstruction of the respiratory tract was significantly slower than with flu A, the result of COVID-19 causing larger damage. Examination of the tissue blades under a microscope also showed a scary in the lung which was more widespread in the lungs infected with SAR-COV-2, which could partly explain the state of breath observed in certain long patients. The study also revealed that the inflammatory response to SRAS-COV-2 resulted in kidney damage which lasted longer than the damage caused by the infection of influenza A.

With Tenoever, the authors of the study of the Nyu Langone Health Microbiology department were the first author Justin Frere, Kohei Oishi, Ilona GOLYNKER, Maryline Panis, Shu Horiuchi and Rasmus Møller. The other authors understood Daisy Hoagland, now at Harvard University, and Randal Serafini, Kerri Pryce, Jeffrey Zimering, Anne Ruiz and Venetia Zachariou in the department of neuroscience; as well as Jonathan Overdevit in the department of neurosurgery.

The authors of the study of Columbia University were Marianna Zazhyska, Albana Kodra and Stavros Lomvardas de Mortimer B. Zuckerman Mind, Brain and Behavior Institute; as well as Peter Canoll of the department of pathology and cell biology. The authors of Weill Cornell Medicine’s study were Alain Borczuk in the department of pathology and laboratory medicine, and Vasuretha Chandar, Yaron Bram and Robert Schwartz in the department of physiology, biophysics and systems biology.